Cleanup

locations at Los Alamos National Laboratory, a Manhattan Project site,

include hillsides, canyon sides, and canyon bottoms. This photo shows

soil cleanup in Los Alamos Canyon, which is adjacent to the former

Technical Area-01 and the center of the laboratory during the Manhattan

Project.

On

July 16, 1945, the world's first nuclear explosion occurred more than

200 miles south of Los Alamos in Alamogordo, New Mexico, in what was

code-named the Trinity Test — a name inspired by the poems of John

Donne.

A

plutonium implosion device was successfully tested at that site 75

years ago. The test indicated that an atomic weapon using plutonium

could be readied for use by the U.S. military.

The

test was completed by staff with the Manhattan Project, whose “secret

cities” — Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington —

were conceived, built, and operated in secrecy as they supported weapons

development during World War II. Today, Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and Hanford are among the sites of EM’s cleanup efforts.

|

The original gate through which workers entered Los Alamos National Laboratory during the Manhattan Project years.

|

Los Alamos

Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) was established in 1943 as Site Y of the Manhattan Project for a single purpose: to design and build an atomic weapon.

While

the scope of work conducted at DOE’s senior national laboratory has

broadened considerably since the pivotal day of the Trinity Test, LANL’s

primary mission has remained nuclear weapons research and development.

While

executing this mission during the Manhattan Project era and in the

decades that immediately followed, LANL released hazardous and

radioactive materials to the environment through outfalls, stack

releases, and disposal areas. Additionally, mixed low-level and

transuranic (TRU) waste was generated and staged in preparation for

off-site disposition.

The

EM mission at Los Alamos is to safely remediate and reduce risks to the

public, workers, and the environment associated with legacy material,

facilities, and waste sites at LANL. Of the more than 2,100 contaminated

sites at LANL originally identified for remediation, more than half

have been cleaned up and closed. Those range from small spill sites with

a few cubic feet of contaminated soil to large landfills encompassing

several acres.

Some

of those landfills were at Technical Area 21, which was a complex of

Manhattan Project and Cold War buildings that housed LANL’s plutonium

processing facility. It was the site of groundbreaking tritium research

for energy, environment, and weapons defense research.

Much of the Manhattan Project and early Cold War operations took place at what was known as Technical Area 01. Perched on a plateau near a canyon edge, the site was LANL’s original footprint and is now part of the Los Alamos townsite. Remediating legacy materials there has been one of EM’s biggest priorities at LANL.

Much of the Manhattan Project and early Cold War operations took place at what was known as Technical Area 01. Perched on a plateau near a canyon edge, the site was LANL’s original footprint and is now part of the Los Alamos townsite. Remediating legacy materials there has been one of EM’s biggest priorities at LANL.

Over

the coming decade, as LANL continues to advance DOE’s national

security, science, technology and energy missions, EM’s Los Alamos

program will remained focused on protecting human health and the

environment by addressing groundwater contamination plumes, processing

above-ground-stored TRU waste, and retrieving belowground-stored TRU

waste at Technical Area 54 for off-site disposal.

An

aerial view of the K-25 Building’s construction at Oak Ridge during the

Manhattan Project. In 18 months, workers built the world’s largest

building, and its gaseous diffusion technology proved to be the

preferred enrichment method during the Cold War.

Oak Ridge

In

1942, the U.S. government acquired land that became the Oak Ridge Site.

By March 1943, 56,000 acres were sealed behind fences and major

industrial facilities were under construction to develop a

first-of-a-kind weapon, and a secret city of nearly 75,000 people arose

almost overnight to support this world-changing task.

During

the Manhattan Project, the K-25, S-50, and Y-12 plants were built to

explore different methods to enrich uranium, while the X-10 site was

established as a pilot plant for the Graphite Reactor and to explore how

to produce plutonium.

Throughout

the following decades, these sites would each go on to push the

boundaries of science that revolutionized power production, enhanced

national defense, advanced understanding in biology and genetics, and

developed new fields of medicine. While these missions were beneficial

to the world, they also created environmental legacies that EM is now

cleaning and removing to enable the next generation of innovation.

The K-25 plant, present-day East Tennessee Technology Park

(ETTP), enriched uranium using the gaseous diffusion process. Due to

the success of this technique, the original plant was expanded during

the Cold War. It contained five enormous uranium enrichment facilities,

including the largest building in the world when it was constructed, and

hundreds of support facilities.

After

nearly 15 years of large-scale demolition and environmental cleanup,

Oak Ridge’s EM program is completing major cleanup at ETTP this year — a

goal known as Vision 2020 and one of EM’s 2020 priorities.

It will mark the first time in the world an entire enrichment complex

has been removed. The site is being transformed into a multi-use

industrial park that offers opportunities for economic development,

conservation, and historic preservation to the community.

After

nearly 15 years of large-scale demolition, EM has cleared away 13

million square feet of aging, contaminated structures at the East

Tennessee Technology Park at Oak Ridge.

Separately,

Y-12 was built to enrich uranium for the first atomic weapon using an

electromagnetic separation process. The Cold War brought change to Y-12

as new processes for separating lithium were added and uranium

enrichment missions were conducted elsewhere.

EM is ramping up efforts that are addressing Y-12’s primary contaminant, mercury. Those efforts include construction of the new Mercury Treatment Facility,

which is now underway, and funding research for new mercury remediation

technologies. Crews are transitioning to the site to begin deactivating

and demolishing its old, deteriorating facilities. This will eliminate

hazards, enable modernization, and provide space for new missions at

Y-12.

The first mission of X-10, present day Oak Ridge National Laboratory

(ORNL), was to develop and test the experimental Graphite Reactor,

which went critical in March 1944. It was used initially as a pilot test

facility for plutonium production. In the years following the Manhattan

Project, 13 research reactors were designed and built onsite, and staff

developed or participated in developing numerous nuclear material

reprocessing methods.

Scientists

there would also go on to research genetics and the biological effects

of radiation. ORNL’s mission continued to grow through the years and has

expanded its capabilities to be at the forefront of supercomputing,

advanced manufacturing, materials research, neutron science, clean

energy, and national security.

EM is supporting ORNL’s missions

by eliminating its inventory of TRU waste and uranium-233, and ramping

up efforts that will deactivate and demolish its large inventory of old,

contaminated facilities. These efforts will eliminate risks, enhance

safety, enable modernization, and make room for the next big scientific

discovery.

Through

EM’s work, these sites have a bright future to continue Oak Ridge’s

rich history of leadership and innovation for the next 75 years.

|

In

this photo from World War II, Hanford's B Reactor can be seen between

the water towers at right, along with other facilities that supported

reactor operations. The reactor began operating in September 1944 and

was shut down from 1946-1948. It then went back into service until 1968.

Hanford

Once

a thriving agricultural area known for its early-to-market fruits, the

area in southeastern Washington State now known as the Hanford Site

transformed almost overnight when the Army Corps of Engineers chose it

in 1942 as the site of the Manhattan Project's plutonium production

facilities.

More

than 51,000 workers from across the nation came to Hanford in just a

few months. In just 18 months, these workers constructed and began to

operate a massive industrial complex to fabricate, test, and irradiate

uranium fuel and chemically separate out plutonium. That plutonium was

used for the Trinity Test, and for the atomic weapon used on Nagasaki,

Japan on Aug. 9, 1945.

Hanford

continued to expand its plutonium production capabilities in support of

the Cold War, ending up with nine production reactors and five chemical

separations plants. For more than 40 years, reactors located at Hanford

produced plutonium for America’s defense program. In 1989, the Hanford

Site mission changed to cleaning up liquid and solid waste, taking down

facilities, and restoring the environment to protect the Columbia River.

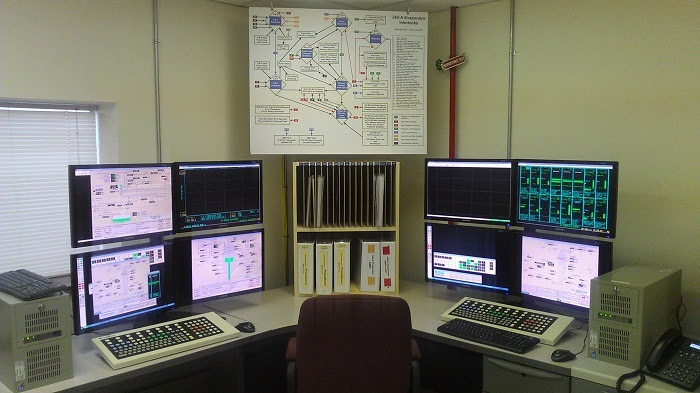

The

control room of the B Reactor gives visitors to this national historic

landmark a glimpse of what it was like to work inside the world's first

full-scale plutonium production reactor.

Since

1989, Hanford has been the site of an extensive cleanup undertaken by

EM in agreement with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the

Washington State Department of Ecology. Since the cleanup of Hanford

began:

- 1,353 waste sites have been remediated and cleared;

- 18.3 million tons of solid waste has been safely collected and disposed;

- 23 billion gallons of contaminated groundwater has been cleaned and returned to drinking water quality.

All of the nuclear reactors associated with the Manhattan Project were decommissioned and safely placed offline.

-Contributors: Bruce Drake, Steven Horak, Ben Williams

The History of a Park Dedicated to the Manhattan Project Story

This

2016 photo shows a view of the Hanford Site's B Reactor National

Historic Landmark, a vibrant tourism and education draw that is part of

the Manhattan Project National Historical Park.

The

Manhattan Project was an unprecedented, top-secret research and

development program created during World War II to develop an atomic

weapon.

The

beginning of the atomic age is recognized as one of the most important

events of the 20th century. Its profound legacies include the

proliferation of nuclear weapons, vast environmental remediation

efforts, the development of the national laboratory system, and peaceful

uses of nuclear materials such as nuclear medicine.

In

2001, DOE worked with the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and

a panel of distinguished historic preservation experts to develop

preservation options for six DOE-owned Manhattan Project-era historic

facilities that the panel found to be of extraordinary historical

significance and worthy of “commemoration as national treasures.”

In

2004, Congress directed the National Park Service (NPS) to work with

DOE to evaluate whether it was appropriate and feasible to establish a

new unit of the national park system dedicated to telling the story of

the Manhattan Project.

After a decade of work by local communities, elected officials, DOE, NPS, and other stakeholders, the Manhattan Project National Historical Park was authorized as part of the Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015.

The park includes facilities at the three primary Manhattan Project locations — Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and Hanford.

The park includes facilities at the three primary Manhattan Project locations — Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and Hanford.

At

Los Alamos, more than 6,000 scientists and support personnel worked to

design and build the atomic weapons. The park currently includes three

areas there: Gun Site, which was associated with the design of the

“Little Boy” bomb; V-Site, which was used to assemble components of the

Trinity device; and Pajarito Site, which was used for plutonium

chemistry research.

A

view of the grand opening of the K-25 History Center at Oak Ridge in

February 2020. The K-25 footprint is part of the Manhattan Project

National Historical Park.

The

Clinton Engineer Works, which became the Oak Ridge Reservation,

supported three parallel industrial processes for uranium enrichment and

experimental plutonium production.

The

park includes the X-10 Graphite Reactor National Historic Landmark,

which produced small quantities of plutonium to support Los Alamos

weapons work; buildings at the Y-12 complex, home to the electromagnetic

separation process for uranium enrichment; and the site of the K-25

building, where gaseous diffusion uranium enrichment technology was

pioneered.

The

Hanford Engineer Works, now the Hanford Site, was home to more than

51,000 workers who constructed and operated a massive industrial complex

to fabricate, test, and irradiate uranium fuel in reactors and then

chemically separate out plutonium to be used in weapons.

The

Hanford landscape is also representative of one of the first acts of

the Manhattan Project — the condemnation of private property and

eviction of homeowners and American Indian tribes to clear the way for

the top-secret work. The park includes the B Reactor National Historic

Landmark, which produced the material for the Trinity Test and plutonium

bomb; and four turn-of-the-century historic buildings that give

visitors a glimpse into the history of the Hanford area before the

arrival of the Manhattan Project.

The

park is managed as a collaborative partnership between DOE, which

continues to own, preserve, and maintain the park facilities and will

work to expand public access to them; and NPS, which administers the

park, interprets the story of the Manhattan Project, and provides

technical assistance to DOE on historic preservation. A memorandum of

agreement between DOE and the U.S. Department of the Interior signed in

November 2015 officially created the park and guides implementation of

the park mission by the two agencies.

|

|

In

this 2018 photo, visitors to the Pajarito Site at Los Alamos learn

about Manhattan Project history. The site includes the Pond Cabin,

Battleship Bunker, and Slotin Building used by scientists developing the

plutonium bomb.

|

While

a key component of the national historical park mission within DOE is

enhancing public access to the park facilities, DOE and its contractors

are also working to develop online resources so virtual visitors and

students can learn about the historic facilities and the Manhattan

Project.

This DOE webpage offers a wide range of in-print, online, and in-person Manhattan Project historical resources. The Department also produced podcasts on the history and impact of the Manhattan Project.

At the Los Alamos park unit, the Bradbury Science Museum, operated by Los Alamos National Laboratory, provides numerous electronic resources,

including an overview of the park and Project Y in Los Alamos, and an

overview of Manhattan Project sites on laboratory land. The Bradbury

Science Museum’s online collections database allows visitors to search artifacts, photos, and historic documents from the Manhattan Project. LANL has also produced a video of historic sites and work to preserve them for future generations.

DOE,

in partnership with a local biking club and the National Park Service,

has sponsored an annual bike ride around the B Reactor at the Hanford

Site, as shown here in this 2016 photo.

Oak Ridge's K-25 Virtual Museum offers visitors information about the Manhattan Project and Cold war.

The

Hanford park unit is accessible to virtual visitors through a variety

of resources, including those provided by partners in the community. DOE

offers virtual access to the B Reactor National Historic Landmark via a

360-degree camera system.

The

Hanford History Project (HHP) at Washington State University Tri Cities

preserves DOE’s federal Manhattan Project and Cold War collection of

artifacts and oral histories. Virtual access to these collections, as

well as the HHP’s collections of oral histories, donated archive

materials, documents, and photographs are available at HHP’s website.

The B Reactor Museum Association provides a series of videos with in-depth information on how the B Reactor functions and why it is recognized as a scientific and engineering marvel.

NPS maintains the official park webpage.

B Reactor: Preserving a Transformative Piece of U.S. History

In

this 2016 photo, schoolchildren explore the B Reactor, a popular field

trip destination for elementary, middle, and high schools. EM’s Richland

Operations Office works closely with educational institutions, tribes,

science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) camps, clubs, and

other interested groups to provide access to B Reactor and customized

tours.

The

atomic age began in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945, with the

Trinity Test — the culmination of the top-secret Manhattan Project.

This

first-ever detonation of a nuclear device led to a new era marked by

the development of weapons with previously unimaginable power, and a

complicated legacy that includes the fields of nuclear medicine and

nuclear energy, the growth of a vital national laboratory system, and EM’s vast environmental cleanup.

The B Reactor at the Hanford Site

was the world’s first full-scale plutonium production reactor, and

produced plutonium for the Trinity Test and one of two weapons deployed

in August 1945 during World War II. B Reactor is now part of the

Manhattan Project National Historical Park. Other historic facilities at

Oak Ridge and Los Alamos are also part of the park.

While

it only took 11 months in 1943 to construct B Reactor, preserving the

reactor and later creating the park took considerably longer.

Nonetheless, the decades-long effort exemplifies what is possible

through strong partnerships among Congress, local communities, DOE

headquarters, EM sites, and other federal agencies.

Former

B Reactor workers sought recognition for the facility’s historical

status, resulting in its designation as a National Historic Mechanical

Engineering Landmark in 1976, and a National Historic Civil Engineering

Landmark in 1994.

With

broad community support, the reactor was added to the National Register

of Historic Places in 1992. In 2008, with DOE support, the U.S.

Department of Interior designated B Reactor a National Historic

Landmark. After a decade of a congressionally mandated study by the

National Park Service and DOE, bipartisan legislation was passed by

Congress and signed into law in 2014 establishing the park.

Community

advocates and local leaders in the three Manhattan Project communities

and elsewhere across the nation drove efforts to preserve the reactor.

For

EM and Hanford, the vision and tenacity of community leaders and

organizations — including the B Reactor Museum Association, the Tri

Cities Development Council, local governments, and Visit Tri Cities —

and the work of their representatives in Congress made the park

possible.

EM

and Hanford leadership safely preserved the B Reactor and supported the

creation of the park, recognizing that providing controlled, safe

public access to the historic facilities over time would be a powerful

educational tool in explaining the EM mission and progress to taxpayers.

More

than 12,000 people typically visit the B Reactor each year, and

international visitors have come from more than 90 countries worldwide,

bringing an estimated $3 million in tourism to the local community.

DOE Honors SRS Team With Excellence Award for Coal Ash Cleanup

AIKEN, S.C. – A team from the Savannah River Site

(SRS) that completed cleanup of coal ash-contaminated land a year early

and at a savings of more than $8 million has been recognized by DOE

with the prestigious Project Management Excellence Award.

The

project team remediated and closed the D Area coal ash landfill, two

coal ash basins, and a coal pile runoff basin. It’s an area consisting

of over 90 acres at SRS used to manage ashes from the D-Area Powerhouse,

which provided steam and electricity for SRS missions for more than 59

years.

The

powerhouse was closed in 2012, and DOE-Savannah River (DOE-SR) and

contractor Savannah River Nuclear Solutions (SRNS) undertook cleanup in

2014.

An

award citation signed by Energy Secretary Dan Brouillette noted the

project team built a strong relationship with the South Carolina

Department of Health and Environmental Control and the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to negotiate a cleanup schedule.

The award was announced at an EM workforce meeting on July 14.

"Not

only did the team come in ahead of schedule and under budget, but

they’re also being recognized for the strong relationship they developed

with the EPA and state regulators," EM Senior Advisor William "Ike"

White said. "We all know how important those relationships are to

achieving success across EM."

"The

success of the SRS D Area Ash Project is a direct result of a sound

closure plan developed by a core team of DOE-Savannah River and SRNS

project managers and supported by our state and federal environmental

regulators," said Michael D. Budney, manager, DOE-SR Operations Office.

"The strategy of a phased approach provided schedule and financial

flexibility and allowed the team to set the standard for how to clean up

one of the biggest environmental problems facing power generating

facilities across the U.S., whether commercial or federally owned."

Before-and-after

photos of the Savannah River Site ash basin cleanup project. Crews

remediated over 90 acres of federal property.

Remediation

was complicated by immense rains from multiple hurricanes. Each inch of

rain resulted in roughly 1 million gallons of stormwater that had to be

managed and pass toxicity testing before it could be discharged.

Despite the challenges, the $65.8 million project was completed in 2019,

a year ahead of schedule and more than $8 million under budget.

"This

mammoth cleanup task consolidated more than 400,000 cubic yards of coal

ash and was completed more than a year ahead of schedule while saving

millions," said Stuart MacVean, SRNS president and CEO. "We were

pursuing performance excellence, safe operations, and timely completion

with this multi-year project, and those goals were not just met, but

exceeded."

The

project team includes Karen Adams, federal project director; Todd

Alasin, project management support with DOE; Brian Hennessey, Federal

Facilities Agreement project manager with DOE; Susan Bell, SRNS project

manager; Julee Smith, SRNS project controls lead; Drew Murphy, SRNS

buyer; and Don Baston, SRNS design engineering.

Each

year DOE recognizes various projects that have demonstrated excellence

in project management. The Secretary's Excellence Award is presented to a

project team that achieves “exceptional results” in completing a

project within cost and schedule.

EM Prepares for Demolition in Heart of ORNL

Crews

are manually adding 12,000 square feet of fabric to the trusses to

complete the cover for the protective tent at the Building 3026

demolition project at Oak Ridge.

OAK RIDGE, Tenn. – The Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management

(OREM) and its contractor UCOR are preparing to demolish the remaining

structures associated with Building 3026, the former Radioisotope

Development Lab.

“This

project is a big step for our program because it marks the beginning of

the next phase of major cleanup in Oak Ridge,” said Nathan Felosi, ORNL

portfolio federal project director for OREM. “Taking down these hot

cells will remove a longstanding risk from the central campus area.”

Workers

are finalizing the installation of a six-story protective tent to keep

nearby research facilities protected while the final two hot cells from

Building 3026 are demolished. Hot cells are thick, concrete rooms that

are heavily shielded to provide researchers protection from highly

radiative material.

Using

a 175-ton crane, crews set a foundation of 92 16,000-pound blocks for

the protective tent. Workers then began using the crane to erect 20

steel trusses to create the frame. To complete the structure, nearly

12,000 square feet of fabric is being added in two sections.

Building

3026 was originally built in 1945 to support isotope separation and

packaging, but it was later used to examine irradiated reactor fuel

experiments and components. The outer structure and four of the

facility’s hot cells were demolished using funds from the American

Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. However, work has continued on

the remaining structures.

Building 3026 was so severely degraded that the outer structure was demolished more than 10 years ago.

A

175-ton crane is being used to install a six-story protective cover to

keep research facilities near Building 3026 safe during demolition.

Last fall, UCOR completed tasks to eliminate contamination pathways

and prepare the remaining structures for demolition. That included

pumping and grouting a 47-foot-long underground transfer tunnel formerly

used to load radioactive material into the hot cells.

The protective tent will be completed this month, and demolition is scheduled later this year.

As major cleanup is completed at the East Tennessee Technology Park, OREM is transitioning its skilled, experienced workforce to ORNL and the Y-12 National Security Complex to ramp up large-scale cleanup at those sites.

Crews

will work across ORNL’s central campus area to deactivate former

research reactors and other radioisotope laboratory facilities in

preparation for demolition. This work will eliminate hazards across the

site and clear land for future research missions.

-Contributor: Susanne Dupes

Next Mega-Volume Saltstone Disposal Unit Taking Shape at SRS

AIKEN, S.C. – The EM Savannah River Site (SRS) landscape is changing again as Saltstone Disposal Unit (SDU) 8 cell construction work is underway.

“SDUs

are a visual reminder of the progress being made toward the

Department’s goal to safely and efficiently dispose of waste at SRS,

making the community and environment safer,” DOE-Savannah River SDU

Federal Project Director Shayne Farrell said.

SDU

8 is the third 32-million-gallon capacity, mega-volume SDU to be built

by liquid waste contractor Savannah River Remediation (SRR) at SRS.

Mega-volume SDUs stand 43 feet high and 375 feet in diameter.

SDU

8 work has moved past preparing the site and installing a mudmat. SRR

is now setting rebar in preparation for placing the two-foot-thick

foundation slab, the step that moves the work on the cell to the

construction phase.

Mega-volume

SDU design and construction is based on the first successful

mega-volume SDU, SDU 6, which entered into operation in August 2017.

Construction of the SDU 7 cell is complete, and it is currently being

internally lined to protect the concrete and provide a robust leak

tightness barrier.

All

SDU work is being executed safely with detailed plans and protocols in

place to meet all federal and South Carolina state requirements for

COVID-19 controls. Worker participation and management review of ongoing

safety practices and protocols is keeping workers safe.

Savannah

River Remediation subcontractor employees set rebar in preparation for

the foundation slab at Saltstone Disposal Unit 8.

SDUs

are the safe and permanent destination for decontaminated salt solution

(DSS) at SRS. Salt waste is decontaminated through processes that

remove radioactive isotopes, such as cesium. The Salt Waste Processing

Facility (SWPF) is scheduled to begin hot commissioning in 2020 — an EM priority for 2020 — and will process up to 9 million gallons of waste per year after.

DSS

is transferred to the Saltstone Production Facility and combined with

materials to form saltstone, which is pumped into SDUs while it is still

liquid and then hardens for permanent disposal. SRR’s mission is to

safely store, treat, and dispose of radioactive liquid waste and

operationally close SRS waste tanks.

Work

leading up to cell construction included a large excavation and the

installation of a lower mud mat on SDU 8, followed by installation of

the high-density polyethylene liner and then an upper mud mat. SDU 8

will be pieced together by placing 25 walls around 208 columns that

support the one-foot-thick roof, then wrapped with nearly 350 miles of

reinforcing cable.

“This

SDU program team, including our DOE counterparts and subcontractors,

are a very talented group of dedicated professionals,” said SRR SDU

Project Manager Jon Lunn. “They continue to work safely to help execute

the SRS liquid waste mission.”

As

a strategic approach to maximize resources, SRR is building SDU 9 in

parallel with SDU 8. SDU 9 cell construction preparation work is in

progress. SDU 8 construction is expected to be complete by February

2023.

Hanford Tank Operations Go Digital to Support 24/7 Waste Treatment

Upgraded

digital technology at the Hanford Tank Farms has eliminated reliance on

myriad white boards, clipboards, and paper. The upgrades have also

improved worker safety and efficiency, simplified operations, automated

data collection, and electronically provided timely and accurate

information to the workforce.

RICHLAND, Wash. – New digital systems have significantly upgraded waste tank operations at the Hanford Site as the workforce prepares to support round-the-clock conversion of tank waste into glass in the site’s Waste Treatment and Immobilization Plant when the complex is operating.

EM Office of River Protection

contractor Washington River Protection Solutions (WRPS) has implemented

a series of digital initiatives over the past several years. They

include a suite of more than 60 software products that provide improved

command and control of operations while reducing repetitive manual data

activities and actions that can generate human error.

“In

the past, we relied heavily on paper records that required more time to

update and generally slowed our ability to communicate compared to

using electronic records,” said Dimple Patel, EM Tank Farms

instrumentation and control safety system oversight engineer. “Today’s

digital technology makes recordkeeping more efficient and communications

much faster, both of which contribute to mission progress.”

The

upgraded digital technology has eliminated reliance on myriad white

boards, clipboards, and paper. The upgrades have also improved worker

safety and efficiency, simplified operations, automated data collection,

and provided timely and accurate information to the workforce.

“We’re

building the infrastructure that will provide critical information

decision-makers need, wherever they are,” said Mirwaise Aurah, WRPS

process and controls systems engineering manager.

Large

wall-mounted touchscreen tablets provide an instant messaging system

covering work activities, weather conditions, sampling plans, event

notifications, and more.

In

a further enhancement, six control rooms scattered throughout tank

operating areas were consolidated into a single central control room.

Through a network of secure wireless systems, technicians in the control

room monitor leak detection systems, tank waste levels, waste transfer

systems, and tank ventilation systems to ensure the integrity and

continued safe operation of Hanford’s waste tanks.

-Contributor: Mike Butler

|

New Equipment Strengthens Environmental Monitoring at SRS |

In

this February 2020 photo, Savannah River Nuclear Solutions (SRNS)

Scientist Jason Walker, left, inspects a new portable air monitoring

station, while SRNS Environmental Specialist Jesse Baxley records

readings from one of several permanent units at the Savannah River Site.

AIKEN, S.C. – The EM program has added two portable units to its network of 14 permanent air monitoring stations at the Savannah River Site (SRS), helping extend the reach of its study of the atmosphere in and around the site.

“The

geographical coverage and the data obtained by these air sampling

stations is excellent,” said Jason Walker, a scientist with Savannah

River Nuclear Solutions (SRNS), the site’s management and operations

contractor. “However, with the purchase of two portable sampling units

we can significantly increase our options, placing these

state-of-the-art portable units wherever needed to add to the

versatility of our overall program.”

The

SRS Radiological Environmental Monitoring Program monitors effects SRS

has on the environment. There is one permanent air monitoring station

onsite, 10 at the site perimeter, and three within population centers

near SRS. Initially, each portable system will be temporarily located

near a permanent station, then scientists will compare the data. The

units will then be placed in storage where they can quickly be accessed

and deployed as needed.

“This

will enable us to make small adjustments to further improve the data

received from each permanent station. A portable unit can also be used

to temporarily collect data while a permanent uni

No comments:

Post a Comment